From record lows just after the Brexit vote – government bond yields have spiked higher. Ten year bond yields have risen from 1.36% in the US to 2.2%, from -0.19% in Germany to 0.31% and from 1.81% in Australia to 2.64% in four months. This in turn has led to sharp falls in high yield share market sectors like real estate investment trusts and utilities that had benefited from the fall in bond yields as investors sought higher yields. The back-up in bond yields has been given an added push by the election of Donald Trump as President of the US. So this all begs the question – have we seen the end of the 35 year super bull market in bonds? What does it mean for investors?

A bit of context

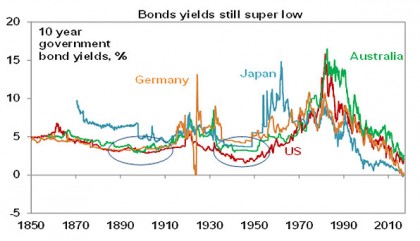

For context, the next chart shows bond yields back to 1850.

Source: Global Financial Data, AMP Capital

So far, while the 0.6 to 0.8 percentage point back up in bond yields seen since their mid-year lows has been sharp, it barely registers as a flick off the bottom in the chart. And note that there has been several back-ups in bond yields through the super cycle bond bull market since the early 1980s that have proved temporary – eg in recent times Australian bond yields rose 2 percentage points in 2009, 1.7 percentage points in 2012-13 (the “taper tantrum”) and 0.9 percentage points early last year – only to see bond yields resume their downtrend.

Bonds 101

Let’s take a quick look at how bonds work. If the government issues a bond for $100 and agrees to pay $4 a year in interest, this means an initial yield of 4%. Obviously the higher the yield the better, but in the short term the value of the bond will move inversely to the yield. If growth or inflation slows and interest rates fall investors might snap up bonds paying 4% till the yield is pushed down to say 3%. In the process the value of the bond goes up giving a capital gain. This is what’s happened in recent years. But, if growth and inflation pick up and bond yields rise, investors suffer a capital loss. And if you buy a bond yielding 3% and hold it for its term to maturity the return will be 3% pa!

Why did bond yields get so low in the first place?

The collapse in bond yields to record lows into mid-year reflected a combination of factors: worries about deflation; investors extrapolating current very low official interest rates into the future; worries that economic growth will remain slow; safe haven investor demand for bonds in response to geopolitical concerns in recent years (eg Ukraine, Brexit); an increasing demand for safe income yielding assets as populations age; a shortage in the supply of bonds as budget deficits fell when central banks have been buying bonds; and yields in higher yielding countries like Australia being pushed towards low yielding countries by investors chasing yield.

So why are bond yields now rising again?

A range of factors are now driving a rise in bond yields:

-

global growth has proved stronger than feared earlier this year – global business conditions indicators are trending up;

-

the threat of deflation is fading and global inflation looks to have bottomed – commodity prices (notably oil) have stabilised or increased and continuing global growth is gradually eating into spare capacity;

-

Donald Trump’s election as President has added to expectations of a “great policy rotation” away from relying on central banks to boost growth to relying more on fiscal policy – with expectations that his policies to cut taxes, boost infrastructure spending and deregulate will boost growth and inflation and allow the Fed to raise rates faster;

-

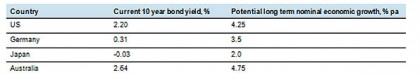

having seen all this investors have then questioned whether ultra low bond yields are sustainable. Over the long term nominal bond yields tend to average around long term nominal GDP growth. And on the basis of our long term nominal economic growth expectations 10 year bond yields are well below sustainable levels;

Bond yields well below long term sustainable levels

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

-

finally, with money pouring out of US equity funds/ETFs for years & into bonds the crowd had gotten too long on bonds.

While there have been lots of premature calls that the bond super bull market that started in the 1980s is over there is good reason to believe that now it is. Bond yields have fallen way below levels that can be fundamentally justified, the threat of deflation is receding, the global economy looks okay and the focus seems to be shifting from monetary stimulus towards greater reliance on fiscal stimulus – led by the US.

Reasons to expect a gradual rise in bond yields

However, this is not likely to be the 1970s when bond yields shot up sharply or even 1994 (when there was a mini bond crash). Rather it’s likely to be a gradual process of base building and rising yields. Historically bond yields have remained low after a long term downswing for around several years, as it takes a while for growth and inflation expectations to really turn back up. This can be seen in the circled areas for US and Australian bond yields in the first chart in this note.

While the Fed is likely to raise interest rates more than currently expected by the money market next year the process of rate hikes is likely to remain gradual as inflation is not a problem, fiscal easing will take time to impact and a rising $US will act as a brake on the Fed. Moreover central banks in Europe, Japan and Australia are likely to continue with existing monetary policy or ease further. As such it’s hard to get too bearish on bonds. At least until inflationary momentum really builds up again and global growth gets up to 4% for a while. But the best is likely over for bonds and the trend is likely gradually up.

What does it mean for investors?

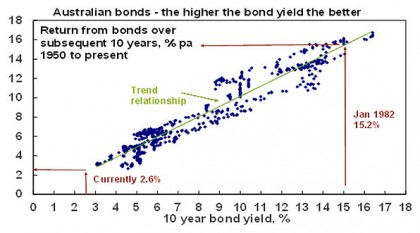

There are several implications for investors from the likely end of the super cycle bull market in bonds. Firstly, while Australian and global sovereign bonds returned around 6% pa over the last three years don’t expect this to be sustained. Over the medium term the return an investor will get from a bond will basically be driven by what the yield was when they invested. This can be seen in the next chart which shows a scatter plot of Australian 10 year bond yields since 1950 against subsequent bond returns based on the Composite All Maturities Bond Index. At 2.6% now we are off the bottom of the chart meaning record low returns for the next ten years. And in the short term rising bond yields will mean capital loses.

Source: Global Financial Data, Bloomberg, AMP Capital

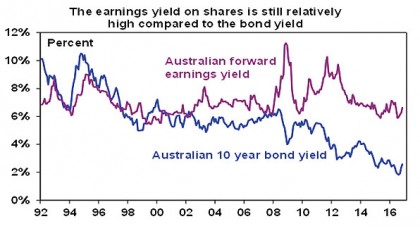

Secondly, a rising trend in bond yields has the potential to constrain the returns on shares as the former make the latter relatively more expensive. However, there are two potential offsets to this. The yield on Australian shares never fell to match the declining yield on bonds – as can be seen in the next chart shares offer a decent risk premium over bonds.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

And if nominal economic growth picks up and this flows through to earnings it will provide an offset to higher bond yields. I suspect that shares will be okay if the rise in bond yields is gradual and so can be offset by rising earnings, but a large abrupt back up in bond yields will be more of a concern.

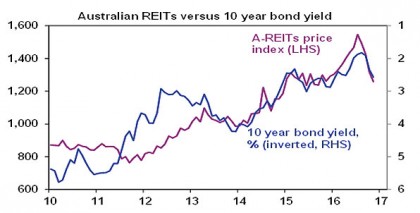

Thirdly, defensive high yield sectors of the share market are likely to remain under pressure. Australian real estate investment trusts and utilities benefitted immensely from falling bond yields (next chart). With bond yields now reversing and cyclical parts of the share market coming into favour, AREITs and utilities are likely to remain relative underperformers.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

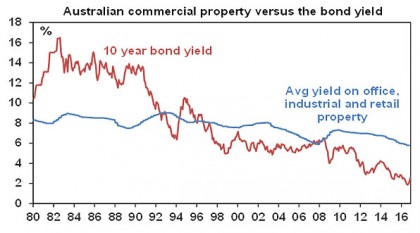

Fourthly, when it comes to real assets like unlisted commercial property and unlisted infrastructure the search for yield is likely to remain a return driver unless bond yields back up dramatically further. As can be seen in the next chart the yield on commercial property has never caught up to the decline in bond yields. Heading into the GFC it was only when bond yields rose above commercial property yields that commercial property prices started to struggle. We are a long way from that.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP Capital

About the Author

Dr Shane Oliver, Head of Investment Strategy and Economics and Chief Economist at AMP Capital is responsible for AMP Capital’s diversified investment funds. He also provides economic forecasts and analysis of key variables and issues affecting, or likely to affect, all asset markets.

Important note: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this article, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This article has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this article, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This article is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided.